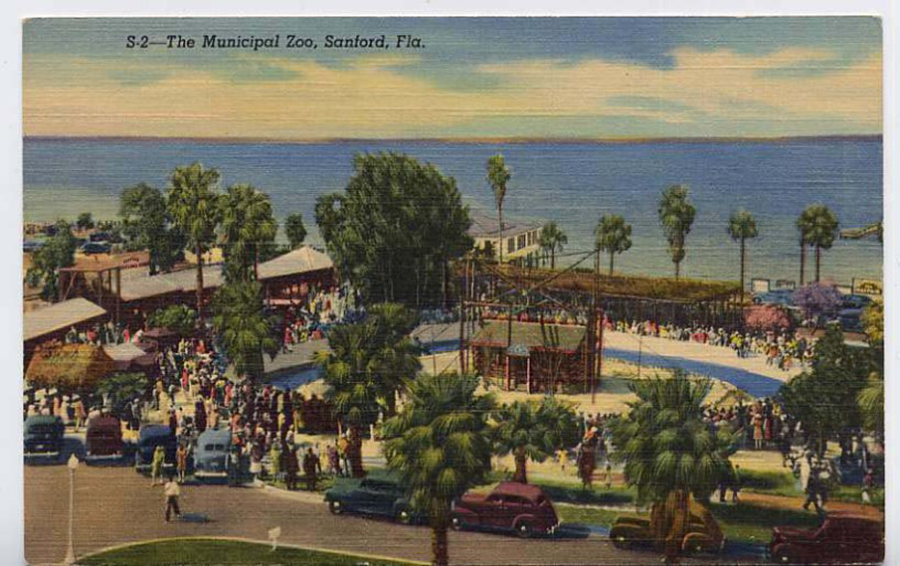

Postcard rendering an overhead view of Sanford Municipal Zoo. Image courtesy of the Sanford Museum.

Years before Central Florida was overrun by a certain mouse, the adoption of a Municipal Zoo in Sanford was a victory for residents. In 1925, the City Commission deemed its new site at the north end of Park Avenue—known today as the site of City Hall. The Zoo transformed Sanford from an agricultural hub to home of one of Florida’s largest tourist attractions.

The Zoo acquired birds, alligators, eagles, otters and more; several of which had been donated by local citizens. When the Rio Vista Zoo in Daytona Beach closed its doors, police bid $30 for a Java monkey and got more—they were gifted a wolf, coyote and several rabbits. By 1927, the Sanford Herald reported a conservative estimate valued $2,000 on the animals alone.

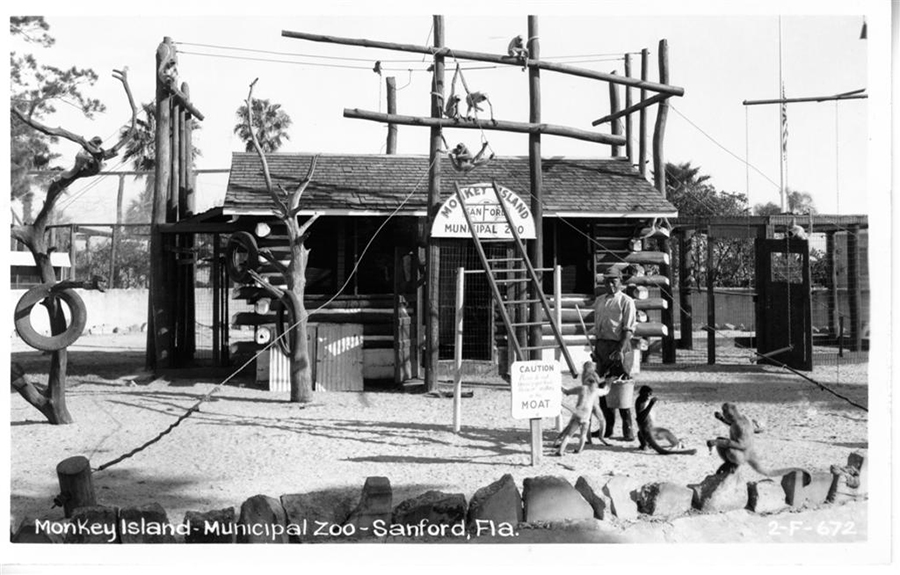

Despite the variety of species, nothing seemed to draw a larger crowd than the ever-popular Monkey Island exhibit which opened in 1940. It was a one-of-a-kind exhibit in the entirety of the Southern states. An apartment with running water was the centerpiece and ladders, cat walks, swings and trapezes jutted out of the building in every direction to provide endless play for all the primates. Surrounding the island was a moat (nothing is more abhorrent to them as water) followed by a brick wall which protected the public while providing an unobstructed view.

Many considered Monkey Island a one-of-a-kind habitat. Image courtesy of the Sanford Museum.

The establishment of a Florida Zoological Society at Sanford was a huge step for the Zoo, providing members who campaigned to secure memberships and raise funds to support growth and improvement. The Sanford Municipal Zoo was booming with visitors, many flocking just to see the Azalea garden (before there was even an established botanical garden). It was common to see 2,000 to 4,000 local residents, other Floridians and out-of-state tourists on any given Sunday. Attention was drawn from every direction and stories about the Zoo were picked up by papers as large at the New York Times.

Trouble came by the start of the 1960’s, when it simply outgrew itself. Relying on city funding to keep up with such a large development presented problems and visitors became weary of the run-down facilities. Though the Zoo had begun to struggle, the economy of Sanford was taking off and the City Commission saw the attraction as an obstruction of growth. They wanted the land for city buildings and decided to shut it down.

Many Zoo residents were animals donated from local citizens. Image courtesy of the Sanford Museum.

Citizens were outraged and the Chamber of Commerce jumped into action, recognizing the reputation of Sanford’s beloved Zoo. Several civic groups came together to save the Zoo but a web of politics impeded any decisions throughout the decade. Plans went back and forth with talk of shutting down, relocating or even abandoning the area completely to open in Orlando.

The Florida Zoological Society secured a federal grant for $100,000 if matched by local funding. Another contingency stated the money would be used for park development—not a Zoo. Seminole County was not interested funding the Zoo, but was looking to develop its recreational parks. They decided the overgrown 104-acre area known as Woodland Park from 1892 to 1920 could be utilized with dual-functionality as a Zoo and recreational park and so the grant was matched.

The new site sat across from Lake Monroe, meaning Sanford’s Zoo was leaving downtown and though it still sat on the edge of the city, its future purpose was to attract all of Central Florida.